Governments looking to deploy social protection programs that combat hunger and poverty want a no-nonsense description of their options and a way to compare each program’s cost and impact. Policymakers and economists have long debated whether it is more effective and cost efficient to give poor and hungry people food or cash.

To help answer this question, the authors of a recent discussion paper, “Cash, Food, or Vouchers? Evidence from a Randomized Experiment in Northern Ecuador”, examine and compare the impacts of three social assistance programs on the quality and quantity of food consumed by a set of randomly chosen households in Ecuador.

The three social protection programs studied were:

• Cash transfers – participants receive a direct deposit of money to an ATM card, which they can use at their discretion.

• Food vouchers – households receive coupons that can be exchanged at local markets for a range of healthy food items selected by the government.

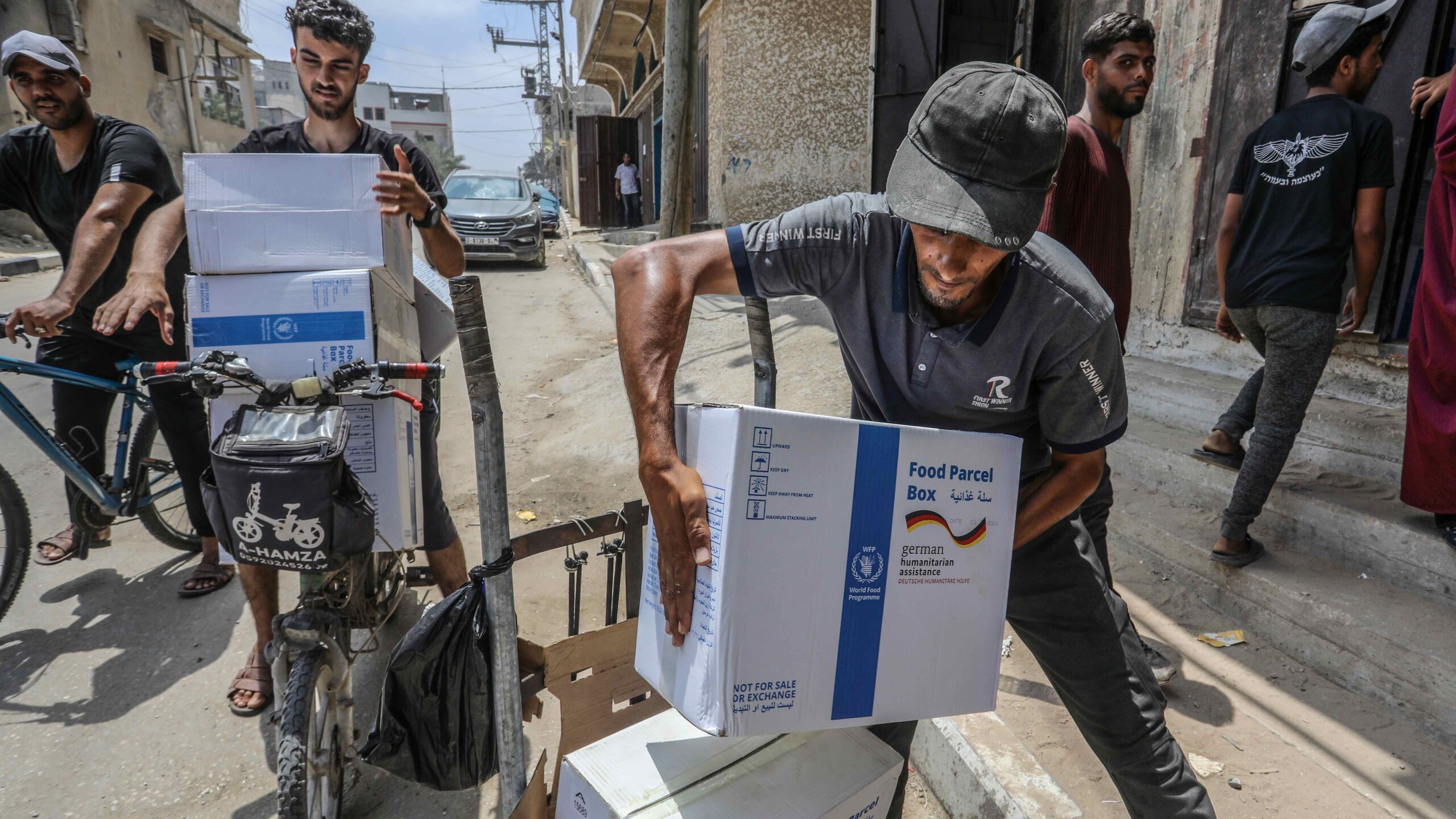

• In-kind transfers – families receive a basket of food that contains healthy portions of staple foods.

The three programs were implemented as part of a World Food Programme project designed to provide assistance to poor people living in seven urban centers in Northern Ecuador. At the same time, they served as a randomized control trial, providing transfers of roughly equal value, distributed across diverse neighborhoods with distinct cultural, socioeconomic, and geographic features.

So how did each type of program measure up?

It turns out all of them work to fight hunger, but there are definitely some winners when it comes to cost effectiveness and nutritional impact.

Coming in last place are in-kind transfers. While the baskets of food helped families fight hunger, they didn’t provide the diversity of nutrition that could be accessed with cash transfers or vouchers. Further, food transfers cost nearly three times more to implement than the other programs. In the authors’ eyes, these two factors made in-kind transfers the least valuable form of social assistance.

Determining the overall winner proved a bit more difficult. Both cash transfers and food vouchers provided the nutritional variety needed to stave off malnutrition, and at a 27-cent difference in price (cash transfers cost $3.03 to implement; vouchers, $3.30) they were both deemed highly cost effective.

Ultimately, the authors decided that the best fit for any given country ultimately depends on the circumstances in that country, and the specific objectives of policymakers.

The perk of a voucher program lies in the government’s ability to direct participants to healthy choices. If policymakers want to improve daily caloric intake and beat malnutrition, they may prefer this option. However, in places without good supermarkets offering a variety of nutritious foods, this powerful tool has clear weaknesses.

That’s where cash transfers come in. These money programs put the power in the hands of the recipient, and, according to studies, people really love that. If policymakers are simply concerned with improving welfare— especially in unstable areas where drought can cause devastation to crops, or where food markets are small and limited—they may decide that recipients can make the best choice for their household at that moment.

To read the entire paper, visit www.ifpri.org.